My Weekend Inside “The Colony”

Snapshot columns look at one specific place or site – what it is and how to get there – against the broader backdrop of its historical (and/or current cultural) context.

At the end of Spring Break travels with visiting friends, I spent a couple of days in Budapest in a smaller, less expensive flat. To my surprise and delight, the space unlocked an entirely new (to me) piece of this city’s history.

My flat was in the Tisztiviselőtelep neighborhood of Pest, in the southeast corner of District VIII. (Budapest, like Paris, is divided into numbered districts – 23 in total.) On Google Maps, hazy gray streets inside the bigger rectangle of streets on a grid intrigued and somewhat confused me – a feeling compounded when I arrived at the address.

Exterior of the MÁV Gépyár Kolónia housing complex along Delej Street (Photo: Julie Strickland)

The apartment complex was massive – spanning an entire city block. The outer wall contained a large courtyard – a typical configuration for apartment buildings in Budapest. What was unusual was the scale, and the use of every bit of space. The outside walls were filled with flats – typical – but unusual were even more buildings with more flats and a conical tower in the center of the courtyard.

The old water tower in the center of the complex (Photo: Julie Strickland)

The scale and density of the homes, while also somehow breezy and open, was unlike anything I’ve ever seen from the period. Most larger housing blocks I’ve seen in Hungary are panelház from the mid-20th century – externally monotonous structures that have gotten something of a cultural boost recently. This was clearly from much earlier. Along the outside walls, flats filled every space. Five floors tall all around, the buildings are walk ups (to use New York parlance) and in the case of my unit at least, airy with high ceilings and large windows.

Inner courtyard of The Colony (Photo: Julie Strickland)

It turned out I was in the former MÁV Gépyár Kolónia, or MÁV (the Hungarian state railway company) Machine Factory Colony. I pieced this together after walking through the even larger former industrial complex across the street in search of Asian supermarkets, which turned out to be the once-site of MÁVAG – the largest Hungarian rail vehicle producer, in operation officially from 1892-1959. (Today the former industrial area is home to a giant Chinese market.)

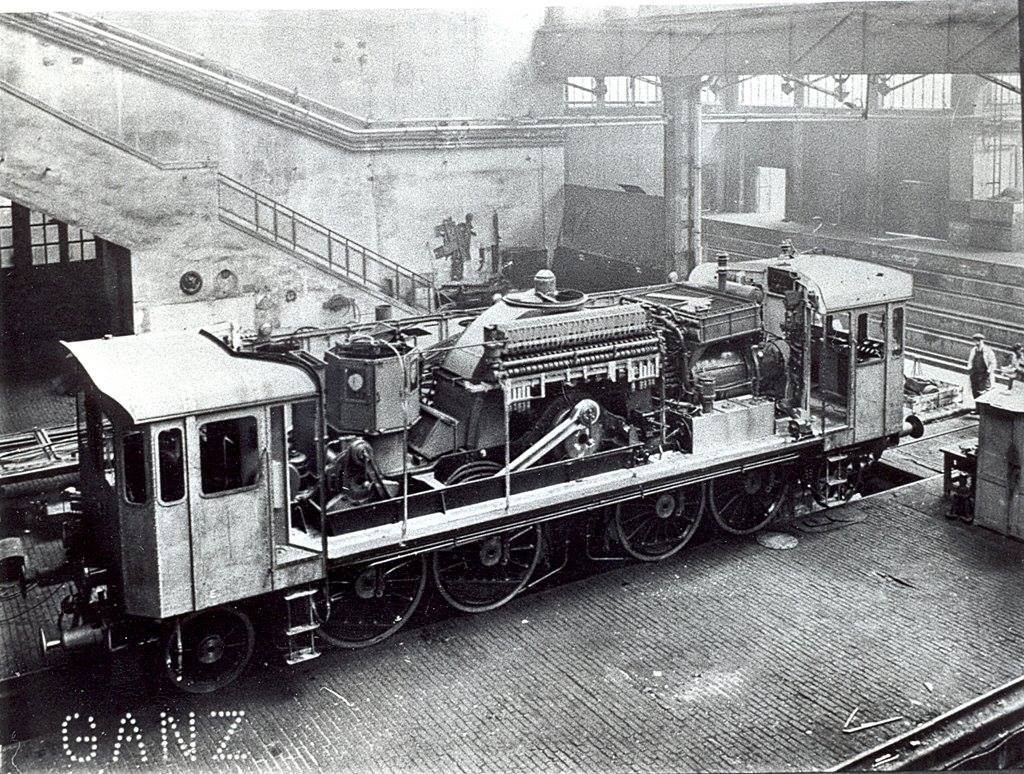

Work at MÁVAG

The need for housing like The Colony – as I’ll refer to the complex from here on out – rose alongside the golden age of rail travel in Europe.

In Hungary, the first railway line was constructed in 1844. The two plants that had produced this early track and the steam locomotives that traversed it were joined in 1870 – becoming MÁVAG. By 1900, the 1500th steam locomotive had rolled off the line. It also produced agricultural machinery and the steel structure of the beautiful Liberty Bridge. MÁVAG’s neighboring company in the complex, Ganz motor és vagongyár (Ganz Wagon and Machine Factory), manufactured diesel locomotives and luxury carriages – mostly for export.

Demand and output peaked from 1892-1914, at which point Ganz and MÁVAG needed a place to house factory workers and company supervisors. The Colony was completed in 1909 and intended to house 3,000 people.

Life in The Colony

The complex contained everything its residents could possibly need: baths, a theater, daycare, clinic, and even a casino. Once upon a time, the water tower in The Colony’s center – which still stands today – served only the complex and its residents.

Floorplan of The Colony, via Quiet / Géza Bencze’s 1989 “The model Hungarian machine industry and training institute for domestic workers”

The building complex consisted of 648 apartments closed into a castle-like circle, with the center only accessible through gates where two lower buildings and the MÁVAG culture houses were located – hosting everything from balls to concerts after the First World War. The workers began to produce cars in the late 1920s, continued to build trains in the 1930s, and churned out military materiel during the Second World War.

A V.40 series locomotive at MÁVAG in 1932, via Magyar Mozdonyok on Facebook

Having lived through the turbulence of two world wars and shifting political regimes, the residents of The Colony formed something of a closed community through the 1950s. During that decade, songs blasted from loudspeakers in the factory to signal shift changes.

The Colony began to open up in the 1960s, after MÁVAG formally merged with Ganz in 1959 and a property management company took charge of the housing complex. From that point anyone could move in, and some units were even designated emergency housing amid ongoing shortages.

The Colony’s Vörösmarty Cultural Center was a hub of art and culture in the following decades. Visual artist Maurer Dóra held workshops there from 1975-1977. The legendary underground nightclub Fekete Lyuk (Black Hole) operated in a basement from the 1980s, a haven for subcultures like punk and metal before and during the regime change of the early 90s.

The building was protected as a monument in the Hungarian capital – a designation like landmark status in New York City – in 1994.

The 1997 musical comedy film Csinibaba filmed several scenes at The Colony. According to the National Film Institute of Hungary, filmmakers love this location because “here time stops – the housing estate has an aura that you can’t find in many places in Budapest.” Director Péter Timár “tried to tell the story of the gray everyday life of the sixties” – a mood The Colony was able to lend in the late 90s.

Still from Timár Péter’s 1997 film Csinibaba, via NFI Nemzeti Filmintézet Magyarország

Today The Colony is a mix of old and new, refurbishment and hipsters alongside families who have been here for generations. It’s an interesting place, palpably full of stories, that few tourists or probably even most Budapestiek get to see.